The sweetness made it weightless

I went to New York, and listened to Laura Stevenson a lot, and got pretty sick but I'm still glad I went

I went to New York City for two months, in August and September, right before moving out of my parents’ house and into my current apartment back in Austin. My heart is still heavy most days, and it was in New York, too, but I haven’t let myself get mired in despair.

Heading to New York marked a shift: although it wasn’t perfect, it was the first significant, positive landmark of my single life. Everything else has felt like that scene in Hot Rod where he falls down the hill, and then he keeps falling down the hill, and then he keeps falling and falling and falling. I onomatopaeia’d it to a friend the other day in a downward “kerchunk kerchunk kerchunk” motion, like tumbling down an “up” escalator. Everything has felt like that since about this time last year, when my marriage ended for real and I moved my shit out on a shitty day when it was pouring shitty rain. And the months wore on, cooped up in my parents’ house, missing my old life and hating my job and doing my best not to succumb to all the quicksand.

And the state washes over me

And the dust from the cars and the cussing in halls

And the trucks and the shards and the spoiling starsMy memory fades,

My memory fades,

And every day

It gets so hot, so hot, so hot

The music of New York singer-songwriter Laura Stevenson has been my companion often throughout the past year, especially the past few months. She sneaks tightly composed poetic meter into meandering melodies, wrapping it all up in a homey haze of soft garage-band guitars and drums. The songs off her self-titled 2021 album, alighting on themes of grief and motherhood, aptly feel like a braid of lullabies and nightmares, all full of dread and comfort and warmth and sadness. Perfect for my late lonely nights of work that makes me feel less than human. Perfect for my heart that needs soothing, but not too sweetly.

I was sick for the whole second half of my time in New York, forced by my body to step back from the reckless edge of my vices, to nap often, to go to bed early. Guiding myself through the avenues and tunnels in a haze of cold medicine. Trying to listen to myself about what I need in a given moment. Still trying, despite the setbacks, to give myself the chance to be weightless for a while. Taking a reluctant crash course in caring for myself, to reckon as lovingly as I could with the animal of my body and the wraith of my mind.

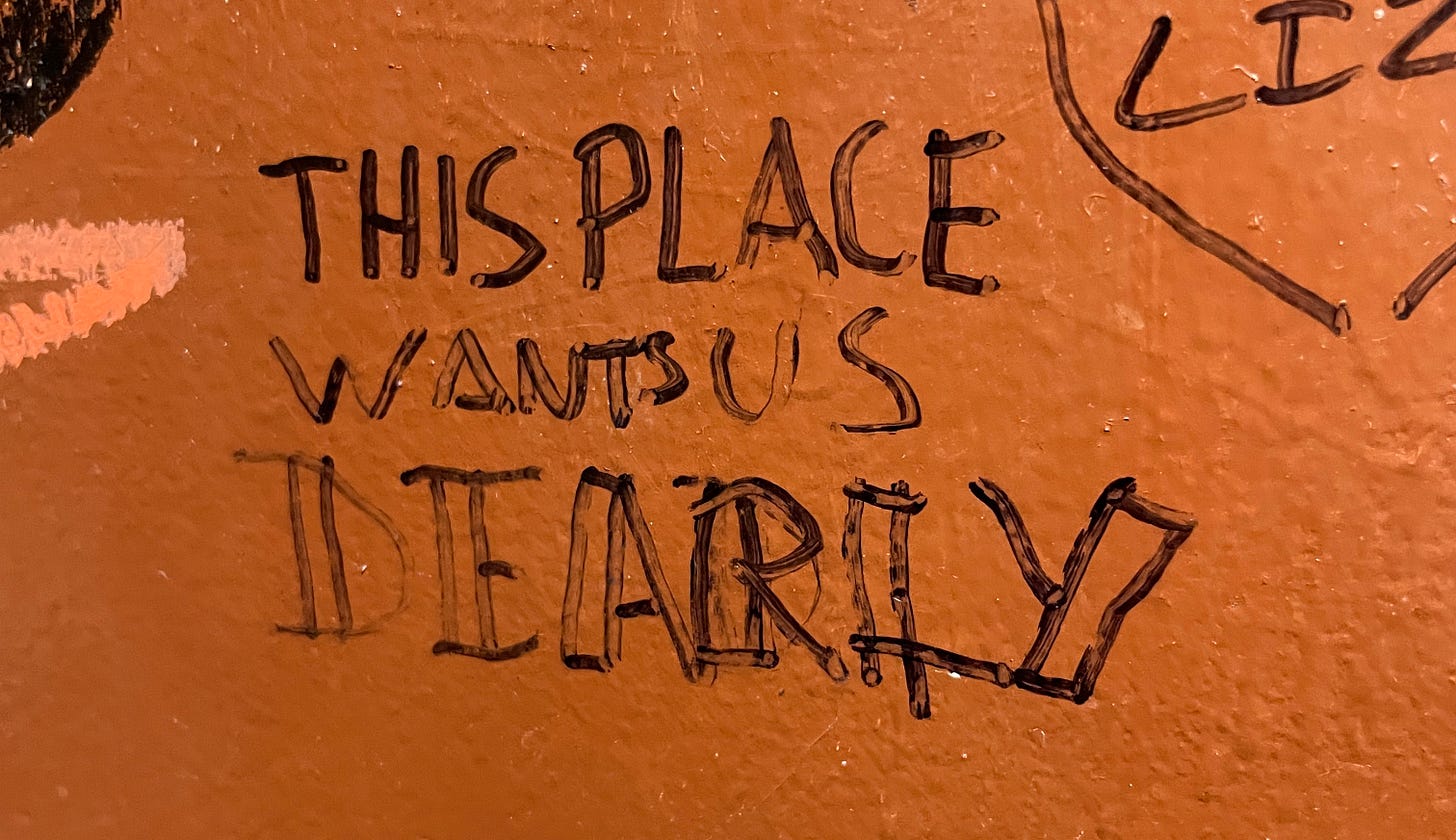

Despite my shattered state, I still saw things you wouldn’t believe, experienced the city’s full litany of miracles. I slept each night in a glowing sanctuary in Crown Heights; I stumbled into a crystal store that sparkled all the way up to the ceiling; I danced with a stranger; I raced my friend’s dog under a full moon. I drank wine on a rooftop at 4 am. I chugged DayQuil and tried to feel young again, before the frightening unknown of my new life in Austin kicked off. I cried and cried, and I felt moments of startling joy, and I freaked out about the state of the world, and I tried to let a few things go.

In “Continental Divide,” Stevenson’s ambitions of care, like mine for myself, hit hurdles:

What could I do right to keep you safe all of your life?

To keep the waves from rising higher than the cities and their sights?

What could I do right to keep you weightless for a while?

You know I’d take this all away from you, I’m trying to

In his 2021 piece on Laura Stevenson, Dan Ozzi wrote: “Pending motherhood allowed her to reflect on the anguish of the difficult preceding year with more perspective, and even some hard-earned peace of mind. She describes the record as a purge and a prayer—at once a primal scream and a meditation on the tranquility that followed. ‘I was looking at the events retrospectively, through this new lens, having this person inside me that I need to protect,’ she says. ‘So there’s this crazy anger, but a serene and protective vibe.’”

Stevenson wrote the album about a close loved one’s traumatic experience, the timeline of which collided with her own pregnancy. It’s a meditation on the roles we imperfectly play for each other, and perhaps even for ourselves, in the wake of disaster.

“With all of my worthiness shook, you stood unmoving / Please, please throw your mercy at me,” she begs some unconventional saint in “Mary.” It’s how I felt in New York, and it’s how I feel being back, as I struggle to believe there are good things ahead. What can I do right to keep myself weightless for a while? To bring back what’s been lost?

It’s sneaky, and impossible to satisfy, this need for restitution. It’s the bargaining stage of grief. Maybe if something new is powerful or fulfilling enough, I won’t have to keep being sad. I trick myself into thinking my grief is a debt that can be paid off, with enough joy or adrenaline or certainty about the future.

“You would say, ‘Hear me, clear voice, my steady foot upon the effete earth / watch me not learn / war of mine, no one dies,’” she sings on “Wretch,” bearing witness to the wild edges of despair amidst gut-wrenching strings.

This is all just a bad dream, right? I’ll pay my dues and wake up and go back to normal soon. If I’m fast enough, I can outrun the sorrow that claws at my ankles. If I’m light enough, I can walk on water.

It’s an urge that’s untenable, but understandable. That spark of self-compassion that shines through the layers of grief and denial is what has guided me out of the darkness, in Austin last year, and then in New York, and now in Austin again. Even without any guarantee, I still owe it to myself to try. To give myself the world in the biggest snowglobe I can afford, to shake it up even when things don’t feel like glitter.

And even though it’s briefly

And though it’s not completely

I can feel you reading

Reading me to sleepAnd oh the water’s beating into me

I’ve left out a lot of things

Hung like trophies stolen in defeat

I watch you wait for me

When no one’s reading me to sleep, I listen to Laura. When the world around me is burning. When the water’s beating into me, I have to remember those weeks in New York. That even when it was stupid or kind of bad, it was also good. And that I’m the one who chose to keep the door cracked open to it.

“I’ll take a small jar of the honey,” I said while paying out at a fabled Yemeni restaurant in downtown Brooklyn I’d forced myself to try, even though I felt like shit.

“Have you ever tried Yemeni honey? It’s from the mountains,” he said with a bit of reserve, but ending with a flourish he couldn’t suppress.

“Fifty dollars for the small, ninety for the large.” Ah, so I understood the reserve.

Instead, he offered me a sample—the little plastic spoon dipped in gold, poised thick and undripping for a moment longer than normal honey would. It tasted rich, a little smoky, compounded by a subtle savory undertone. I understood, then, why a jar cost $50. A taste was enough, though. For a moment the sweetness made me weightless.

New subscriber and fellow Austin denizen.

Great stuff as always (not the being sick, obvs)! You have a a talent for painting incredibly vivid pictures with words.